By Amel Zahid and Natália Mazoni Silva Martins

Recently, as we celebrated the International Day of Older Persons on October 1, we took a moment to reflect on the support given to the elderly population, in particular older women. At the World Bank’s Women Business and the Law, we have a unique opportunity to collect and analyze global data on the status of women’s economic opportunity in 190 economies, including their ability to enter the labor market and save for old age. This wealth of data provides us with great insights and enables us to ask timely questions: Are we truly supporting all older persons, or are we neglecting half of the world’s population – women?

The inadequacy of one-size-fits-all pension schemes

Women’s distinctly different career paths, often shaped by caregiving responsibilities, career breaks, and informal sector employment, reveal the inadequacy of a one-size-fits-all pension schemes. These systems, inherited from an industrial era focus on continuous, paid work, fail to account for women’s lower labor force participation, the persistent gender pay gap, and longer life expectation. As a result, women are left financially disadvantaged in retirement. The gender pension gap is further exacerbated by employment patterns and social norms that limit women’s employment opportunities in the formal sector and reduce their ability to save for retirement, emphasizing the need for pension reforms that consider these diverse realities.

Impact of caregiving on pension benefits

Data from the latest Women, Business and the Law 2024 report finds that, in 81 out of the 190 economies surveyed, time taken off work to care for children – for example, during maternity, paternity, or parental leave – is not considered for the purpose of calculating pension benefits. Offsetting mechanisms such as these are essential to safeguard women’s retirement income. Empirical research suggests that without these compensating mechanisms, women face significant losses in retirement, with replacement rates decreasing by three to seven percentage points on average.

Disparities in retirement ages

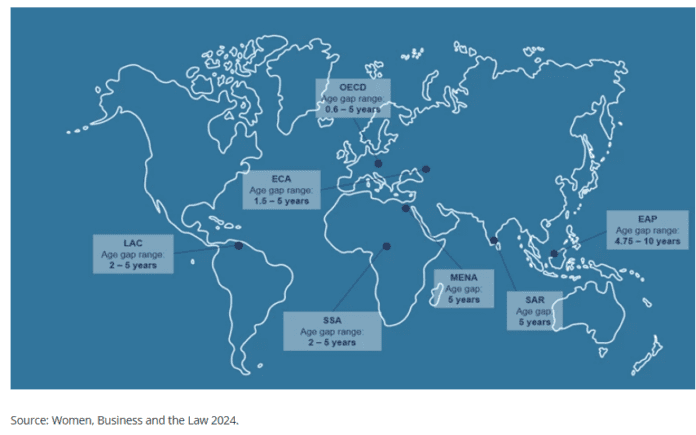

Disparities in retirement ages may also impact women’s ability to sustain their livelihoods after retirement. Early retirement may reduce women’s working lives and impact their contribution records, resulting in fewer earnings in old age. However, in 62 economies, women and men cannot retire and receive full pension benefits at the same age, with women often retiring earlier. There is considerable variation in the age gap ranges by regions. For example, the pension age gap in China is 10 years, in contrast to 7 months in Lithuania (see Figure 1).

Incentives to increase women’s retirement benefits

On the other hand, 29 economies provide some form of incentive to increase women’s retirement benefits. Incentives can include tax breaks for voluntary savings, contributions to be carried forward, subsidies to join a pension scheme early, and accounting for periods of educational attainment in the calculation of pension benefits. For example, the United Kingdom offers tax breaks for voluntary savings with automatic enrollment to increase women’s retirement savings rates. Chile and Spain provide child bonuses and contributory pension supplements to reduce the pension gender gap. Meanwhile, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Poland, and Tajikistan consider noncontributory periods of study at a higher education institution in the calculation of pension benefits.

Progress in addressing the gender pension gap

The good news is that countries have made progress in addressing issues that contribute to the gender pension gap over the past five years. Countries in the MENA region have led in this area. Bahrain, for instance, equalized retirement ages and now explicitly accounts for periods of childcare interruptions in the calculation of pension benefits, while Saudi Arabia and Qatar have both equalized retirement ages for men and women. Countries in other regions have also made progress. In 2024, Sierra Leone obtained a perfect score in the Pension indicator by explicitly recognizing childcare periods in pension benefit calculations.

Challenges and the need for gender-sensitive policy interventions

Over the past two decades, more women have entered the labor force, and the gender pay gap is decreasing by 0.24% on average every year. Global health crises and conflicts now jeopardize this progress, particularly as women are disproportionately employed in heavily impacted sectors – such as services and caregiving – and often hold part-time jobs that are more vulnerable to layoffs. These challenges underscore the urgent need to future-proof safety nets for older women by adopting gender-sensitive policy interventions. Such policies must consider the unique factors that impact women’s ability to save for old age (see Figure 2).

Designing pension systems to reduce gender inequalities

Understanding each country’s specific needs and constraints in terms of fiscal sustainability, labor market access and societal constructions is key to identify legal and policy considerations that can be adopted to address the pension gap. Using data and evidence, such as the ones produced by Women, Business and the Law, can be an excellent starting point in designing pension systems that reduce gender inequalities and benefit not only women, but everyone.