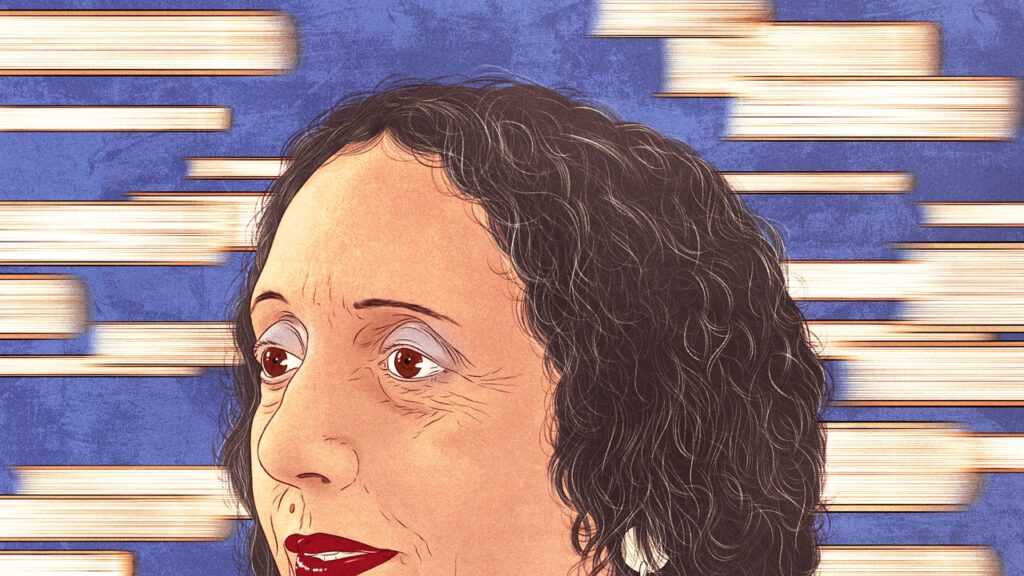

Like many people, the novelist Garth Risk Hallberg was daunted by the size of the celebrated American writer Joyce Carol Oates’s body of work, which encompasses dozens of novels and hundreds of short stories. “I think what everyone feels with her is trepidation,” he said. “You think, What if I don’t like it? And then you think—worse—What if I do?” In the event, Hallberg quickly became a fan, though he admits that he still finds it difficult to summarize her appeal: the trouble with pinning Oates down is that “she’s about, like, ten different things,” including gothic stories, crime novels, and—his favorite—the attempt “to represent the pressure that circumstance and history places on the individual.” Not long ago, Hallberg selected a few recommendations from Oates’s œuvre for us. His remarks have been edited and condensed.

I Lock My Door Upon Myself

by Joyce Carol Oates

Before last summer, the only Oates I had read was the one short story that everyone reads, “Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been?” I think I was seventeen. I remembered it vividly, for years and years. Its signature is a sort of “you are there” quality, in which the reader is not really being guided about what to think or how to interpret the events. There’s a lot of power in that. Then I read this novella, from 1990, in a Granta anthology edited by Richard Ford, “The Granta Book of the American Long Story.” And I thought, Holy shit. This has a lot of the vividness I remembered from “Where Are You Going,” but extends it into this very full-dressed drama, where you get a full picture of a woman’s life from childhood to old age. The writing is truly gripping.

them

by Joyce Carol Oates

This is the first book of hers I read that just had me by the throat from page 1. I think it has one of the great endings in the twentieth-century American novel. I read it because I’m in a book club where we read long books and, after finishing “Anniversaries,” by Uwe Johnson, embarked on Oates’s Wonderland Quartet, of which this is the third installment—the others are “A Garden of Earthly Delights,” from 1967; “Expensive People,” from 1968; and “Wonderland,” from 1971.

It’s a very loose quartet, in the manner of Philip Roth’s American Trilogy. Violence and family are at the center of each book. Three cover the same time span, starting around the Depression and running into the sixties. They also share a very deep and astute concern with social class, which I sometimes feel is the missing element in a lot of American fiction. You can feel Oates’s ambition here is to have a Balzacian command of many different levels of class and, though she can’t quite get it at the upper registers yet—thirty years later, she will—she writes really persuasively and well here about poor people and working-class people, and people’s movements between those strata.

Blonde

by Joyce Carol Oates

“Blonde,” which is from 2000, is among Oates’s longer books, which is sort of frustrating because it is also among her best—it would be the thing that I recommend first, but I don’t know about its approachability. (I’d probably say a new reader should begin with the collection “High Lonesome,” and, in particular, with the story “Small Avalanches.”) It’s a fictionalization of Marilyn Monroe’s life—or, the life of Norma Jeane Baker, as she was actually named. I don’t tend to read historical fiction, but to me, this is much more akin to really accessible experimental fiction, like “Underworld” or “Mason & Dixon.”

Of all Oates’s novels that I’ve read, I think this one has the most depth of character. Monroe just feels like a real person. I was surprised—I did not expect it to be as consistently powerful as it is, page after page. But it is. One thing it really conveys is Oates’s sense of the individual and individual psychology, which is totally sui generis. I think she has a deep intuition about personality as something diffuse and fragmentary, something that we are dressing up every morning in presentable clothes and pushing out into the world as if it were a coherent thing. Do I agree with this view? Not necessarily. But it’s really interesting and compelling to slip it on for a while. And that’s why I think “Blonde” is somehow central to her œuvre—because in the person of Marilyn Monroe, it’s easy to see how, on the one hand, she’s a particular personality, and how, on the other, as you stay with her for the duration of the novel, she’s not just any one thing.