Astronomers have lengthy questioned how Earth turned water-rich—bountiful with abyssal oceans, frigid glaciers and rain that pours from the sky into lakes, rivers and wetlands. Water, which consists of the primary and third commonest components within the universe, is a deceptively easy molecule to kind. But whereas the main points of its supply to rocky planets like our personal could also be important for understanding life’s cosmic prevalence, they continue to be principally unknown.

Water is a potent medium for the meeting of advanced natural molecules and affords havens for the emergence and subsequent evolution of life as we all know it. Deep inside Earth it ensures the lithic lubrication that retains climate-stabilizing plate tectonics from grinding to a halt—one other mechanism that simply may be essential for all times. And when frozen as ice it performs a key position in planet formation by offering the glue that helps younger worlds develop. As such, scientists are anxious to raised perceive water’s planetary peregrinations—the pathways it takes to remodel planets from desiccated rocks into worlds as soaked as Earth.

To achieve extra perception, astronomers are using the James Webb Area Telescope (JWST) to look into protoplanetary disks: the swirls of gasoline and dirt round younger stars the place planets are actively forming right now. Though astronomers have glimpsed water inside such disks earlier than, their view has been hazy. For instance, water vapor is seen to the Atacama Giant Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA)—in lots of respects probably the most highly effective radio observatory on Earth—however the facility largely can’t detect water ice. This blocks a protoplanetary disk’s outer areas from ALMA’s scrutiny. The array additionally can’t deeply probe the new, interior areas of disks the place terrestrial our bodies kind. JWST, however, was designed with such research in thoughts and has—fairly actually—opened the floodgates. The brand new area observatory is delivering unprecedented appears at how water passes from star-forming large molecular clouds into protoplanetary disks and at last onto planets—with important implications for astrobiology, together with whether or not our personal watery world is one way or the other particular or commonplace.

On supporting science journalism

In the event you’re having fun with this text, contemplate supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you might be serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales concerning the discoveries and concepts shaping our world right now.

“With JWST it’s like immediately you strive on new glasses, they usually offer you a a lot sharper view,” says Andrea Banzatti, a Texas State College astronomer finding out protoplanetary disks.

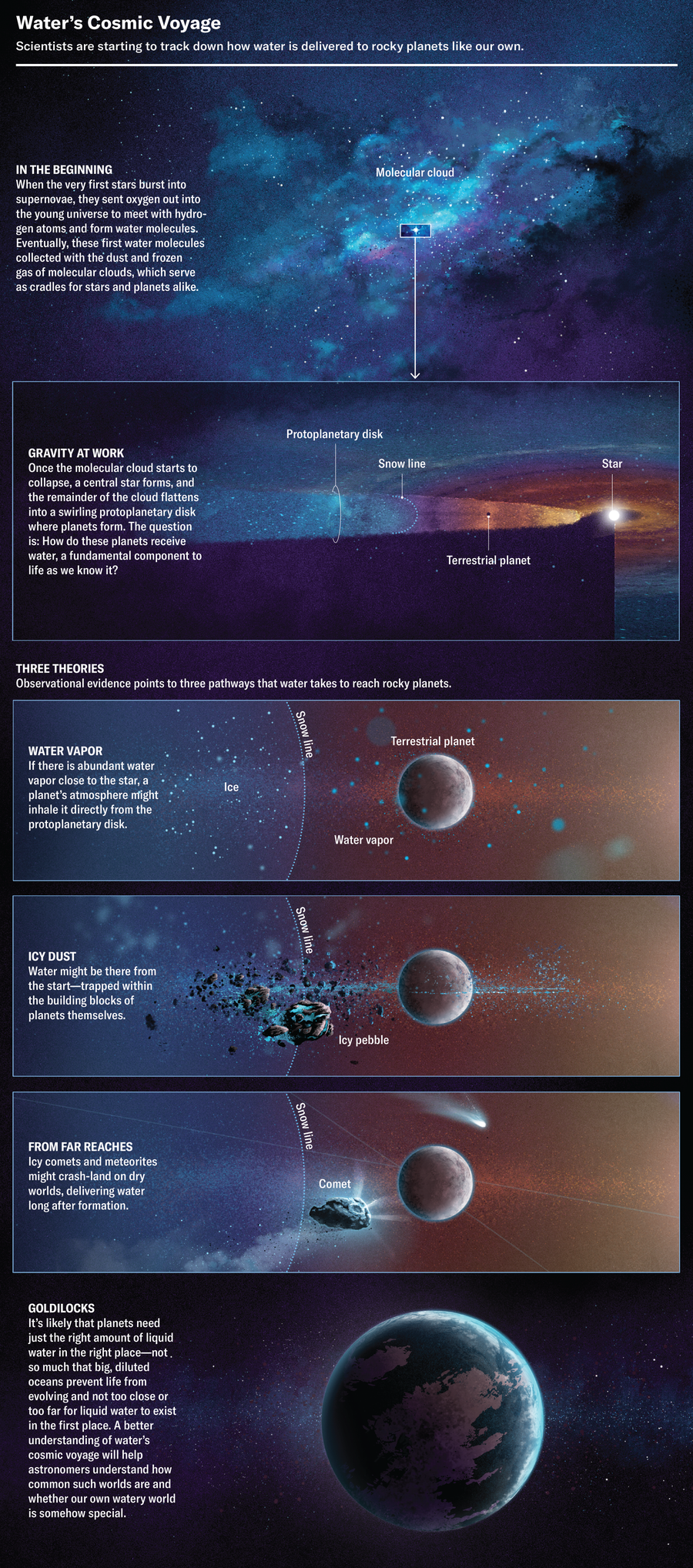

Water’s cosmic odyssey started a whole bunch of hundreds of thousands of years after the large bang. That’s when the primary stars—which had furiously fused by their hydrogen retailer to churn out heavier components—burst into supernovae that seeded the universe with oxygen. At this level, a single atom of oxygen may mingle with two hydrogen atoms to kind a molecule of water—a molecule that would, in a cosmic cycle of creation and destruction, nonetheless be sundered anew by high-energy radiation from stars and different astrophysical sources. But in the end—undoubtedly billions of years later, in some instances—such water discovered its solution to the chilly confines of molecular clouds, the place one other chaotic and violent chapter of its journey would start. Molecular clouds are large, chilly clumps of mud and frozen gasoline that include ample water ice and function cradles for stars and planets alike. When a part of a cloud reaches some important density, gravity causes that dense, roughly spherical area to break down right into a flattened, whirling protoplanetary disk with a nascent, glowing star at its heart. A lot of this course of is obscured by mud and has proved virtually unattainable to probe—till JWST. “It took JWST’s unbelievable sensitivity to allow us to catch the few photons that make it by and therefore characterize the icy grains proper earlier than the onset of star and planet formation,” says Karin Öberg, an astronomer at Harvard College.

From there, the rising star feeds on materials raining in from its enveloping disk, creating extra mild and warmth—and probably breaking up the disk’s water molecules to bake off moisture that will have in any other case flowed into worlds. If this course of occurs too effectively, the consequence can be galaxies filled with parched planetary programs, and we’d effectively not be right here—which is in no small half why most scientists suspect this will’t be the case. By some means water should cross unscathed from placid molecular clouds by scorching star-forming disks.

In 2021 John Tobin, an astronomer on the Nationwide Radio Astronomy Observatory, and others used ALMA to watch V883 Orionis—a disk-wreathed protostar situated 1,305 light-years from Earth that’s solely barely extra large than our solar however shines roughly 200 occasions brighter. The protostar’s radiance heats up the frigid outer disk, reworking ice to water vapor that turns into a beacon for ALMA’s radio imaginative and prescient. It was a fortunate break. Tobin’s group noticed excessive ratios of semiheavy water—during which the heavier hydrogen isotope deuterium substitutes for one in every of a water molecule’s two customary, lighter hydrogen atoms. As a result of semiheavy water can solely kind in chilly temperatures—and never the excessive temperatures straight related to star formation—its origins round V883 Orionis should date again to the molecular cloud itself, suggesting that the water had handed by the star-formation course of unchanged. Certainly, the ratio of semiheavy water to regular water that Tobin and his colleagues noticed completely matched the proportion noticed in different molecular clouds. It additionally matched the ratio present in our photo voltaic system’s comets—hinting at a technique that water can attain rocky worlds.

Astronomers at present suppose that terrestrial planets can achieve water in three other ways. It may very well be that water is there from the beginning—cocooned inside grains of mud which can be the very constructing blocks of the planets themselves. Or maybe the rising planets siphon water vapor straight from the gasoline within the primordial disk—permitting gravity to construct a moist environment round their rocky core. Or perhaps as soon as the planets have fashioned, they guzzle water imported through leftover icy particles falling in from far-flung areas of the planetary system. Tobin’s outcomes counsel that this latter pathway performs a distinguished position however that water-delivering comets and meteorites don’t work alone. Water on Earth has a barely decrease ratio of semiheavy water to regular water than that present in comets—that means that whereas a lot of our planet’s water arrived from the outer photo voltaic system’s icy hinterlands, some will need to have as a substitute been uncovered to excessive temperatures close to the solar. Simply what that publicity appears like, nevertheless, stays an open query.

To search out solutions, Öberg desires to construct a cosmic map—pinpointing the places of water round these younger protoplanetary disks to see the place it’s available to feed any forming worlds. ALMA has already sketched a blurry picture, and JWST is starting to fill within the gaps with spectacular element. Final April Sierra Grant, an astronomer on the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics in Garching, Germany, and her colleagues used JWST to observe water in a disk that had beforehand appeared dry—demonstrating the area observatory’s outstanding functionality to wring contemporary insights even from well-studied programs. “We’re actually in a brand new period with JWST,” Grant says. “It’s outstanding that we may detect issues that we couldn’t detect earlier than.”

Then final August Giulia Perotti, an astronomer from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy in Heidelberg, Germany, and others detected water vapor in PDS 70—the only protoplanetary disk but identified to harbor not one however two large planets. Their presence seemingly signifies that terrestrial planets are additionally coalescing throughout the interior disk—on the exact location the place astronomers have now discovered water. “That is the primary time we’re detecting water vapor within the central areas of a planet-hosting disk,” Perotti says. Earlier observations had proven no water in any respect—which was unsurprising, provided that water can be hard-pressed to outlive the extraordinary radiation so near the star. Now astronomers know that it may and that it could simply glom on to the atmospheres of planets as they develop—versus reaching dry planets through interplanetary guests in a while. As such, most terrestrial worlds throughout the cosmos may be born wealthy, with a wealth of water from the very begin.

That by itself may very well be an issue, Öberg says, that would result in worlds which can be too water-rich. Scientists at present suppose that ocean worlds will battle to create life, however a planet with pond-peppered continents can have a lot better luck. That’s as a result of lots of the reactions thought essential for prebiotic chemistry and the rise of advanced chemical programs proceed way more effectively in small, concentrated ponds than in expansive, diluted oceans. Furthermore, minerals that erode from the continents will add essential vitamins to the water. However to find out how usually the universe builds terraqueous orbs like Earth, Öberg argues that we first want to know younger protoplanetary disks—by finishing that cosmic map, which reveals not simply the places of water round these disks but additionally the way it flows from one locale to the following.

Simply how water pours from the icy outer area of the disk inward, nevertheless, has been unclear—particularly in PDS 70, the place there’s a giant hole between the outer and interior disks. Then final November Banzatti, Öberg and others noticed water vapor throughout the system’s snow line, the transitional area the place shifting temperatures rework water from strong to liquid or gasoline. This confirmed a bodily course of whereby water migrates inward. Forty years in the past, astronomers postulated that water ice within the outer disk would drift inward on sturdier strong materials—mud grains and so-called icy pebbles that vary in measurement from just a few millimeters up to some meters—till sublimating on the snowline in an incredible fog of water vapor. That’s the exact signature that Banzatti noticed. “That is precisely what was anticipated on this basic idea of planet formation, this ‘pebble drift’ state of affairs that ought to feed the formation of [terrestrial planets] and even ship water,” Banzatti says. “From that little sign we are able to construct a fantastic story.” And it has implications for PDS 70. Perotti suspects that this mechanism carried water inward earlier than the hole fashioned between the outer and interior areas of the system’s disk. Or it may very well be that water continues emigrate by the hole even now, albeit on a lot smaller as-yet-unseen micron-sized icy mud. This mud, together with some water molecules, can act as a protecting protect, conserving many water molecules from breaking up.

Öberg’s cosmic map is thus turning into increasingly more detailed—with huge reservoirs discovered in lots of areas of protoplanetary disks, suggesting that water could effectively circulate to rocky worlds in myriad methods. However nonetheless, astronomers have no idea if one state of affairs has the higher hand. “At this stage of our analysis, we aren’t within the place of being unique,” Perotti says. In PDS 70, for instance, it may very well be that these terrestrial planets lose among the water that’s available to them—counting on asteroids to later replenish it. Future observations ought to make clear the dominant pathway, which could change relying on sure traits of the planetary system.

Grant, for instance, is keen to see how water’s dynamics scale with stellar mass. Up to now, high-mass stars look like principally dry⁠ whereas smaller, extra sunlike stars look like comparatively waterlogged, however Grant desires to know what’s typical for among the most diminutive stars. Referred to as M dwarfs, these stars are faint, that means that planets circling them should be in an in depth orbit to be heat sufficient for all times—a quirk that makes them comparatively straightforward for planet hunters to analyze utilizing JWST and different telescopes. Their protoplanetary disk has lengthy appeared water-poor—however contemporary information now counsel in any other case. Final December Banzatti, Öberg and their colleagues printed a research detailing the primary case of a water-rich disk round an M dwarf star. Grant plans to probe this query additional by exploring as many small stars as she will be able to. In the meantime Banzatti’s ongoing evaluation of snowlines from 30 totally different programs is already revealing that small, compact disks ship 10 occasions extra water towards their interior areas than giant, prolonged, gap-filled disks can handle. Water’s cosmic journey is, ultimately, coming into focus.

“It’s actually thrilling to see these outcomes coming collectively,” Tobin says. “It’s an astounding time of discovery—but we’ve actually solely scratched the floor of what’s on the market.”