As increasingly more adoptees get revealed or share their tales, the response from readers and gatekeepers in kidlit publishing is commonly fraught with harm emotions and a restricted understanding of the nuances of the adoptee expertise. On this dialog, Shannon Gibney and Mariama J. Lockington—two authors, students, and transracial adoptees—dive into how this rigidity impacts their lives, their group constructing, and the tales they inform.

As increasingly more adoptees get revealed or share their tales, the response from readers and gatekeepers in kidlit publishing is commonly fraught with harm emotions and a restricted understanding of the nuances of the adoptee expertise. On this dialog, Shannon Gibney and Mariama J. Lockington—two authors, students, and transracial adoptees—dive into how this rigidity impacts their lives, their group constructing, and the tales they inform.

___

SG: So I wish to discuss to you, Mariama, about representations of adoptees in kidlit, notably transracial adoptees, or TRAs. As a Black TRA who regularly writes characters who’re Black TRAs…as a essential thinker, group member, and scholar…what are your total ideas about that?

ML: Yeah, so many ideas! Rising up, I don’t suppose I encountered a guide with a personality that had an analogous illustration as me. Now that I write for younger folks, and I write concerning the nuances of the adoptee expertise, I’m much more essential…I like to learn YA and center grade, and even typically image books only for my very own analysis and pleasure studying. And I’ve to say, I’m much more essential after I encounter adoptees in kidlit that aren’t written by adoptees, and have perhaps completed minimal to no analysis concerning the adoptee expertise. I’m instantly turned off. And it’s onerous for me to remain inside the story as a result of I believe that there’s a number of…It’s simply actually one-dimensional on the subject of these characters and people tales. And in addition, usually problematic. I believe I’ve encountered extra Korean adoptees inside tales for younger adults, and a number of occasions I’m additionally turned off when it’s like, “Oh, this character is adopted, however she loves her household, and it doesn’t have an effect on her.” And it’s simply type of a brush over, and there’s completely no nuance or understanding.

SG: I’d prefer to drill down a bit of bit extra, and ask you: What are the precise sorts of tropes of adoption that you simply usually see deployed in kidlit? I see a number of the dominant tales of adoption on this area as precisely what you say: Love can conquer all, the colorblindness narrative…

ML: Extra love, such as you get two occasions the love, which I hate.

SG: [laughs] Yeah.

ML: I see a number of, “Properly, she’s adopted, however household isn’t about blood, or no matter.” In books the place there’s a reunion of kinds, that can also be very watered down, or the primary dad or mum is useless, which could be very handy.

SG: Yeah, delivery mother and father are just about erased in these tales.

ML: Beginning mother and father are nearly nonexistent, and if they’re there in any respect, the trope is, “Properly, they gave you a greater life. Or, they did a selfless factor. Or, they beloved you a lot they gave you away.”

SG: We are able to discuss non-adoptee writers utilizing these tropes, which occurs lots. But additionally, I really feel just like the tales that are likely to get by means of the publishing course of (and publishing isn’t straightforward, as we all know…It’s actually an endurance sport, and it’s about entry), it does develop into very clear which tales are palatable and which tales usually are not palatable. I’ve heard tales and I’ve had experiences the place a white adoptive dad or mum, normally a white adoptive mom is an editor at a publishing home, and is like, “Properly, that is nice writing, however I don’t perceive why this story is all about race. And why is that this character so indignant? My Chinese language daughters won’t ever blah, blah, blah…”

ML: Oh my God.

SG: I simply had any person inform me that this was the suggestions that they obtained from potential publishers on their memoir. And that is 2024. So, it does typically really feel like a minefield. However even nonetheless, there’s simply much more adoptee BIPOC kidlit writers who’re actually taking these items on in the present day and flipping the script in essential methods, however there are additionally these books which can be popping out sometimes by adoptees that simply reinscribe these identical problematic tropes that we’re speaking about. So, it does really feel very fraught in that manner.

ML: Properly, I believe that’s additionally the onerous a part of navigating the publishing trade as an adoptee author, and as a BIPOC adoptee author. Hopefully, you discover an editor that you simply really feel secure with and cozy with, however you don’t know alongside the method whose emotions may get harm by the nuanced experiences that you simply’re placing into your characters. I’ve a very good relationship with my editor, however I believe she was stunned when For Black Ladies Like Me obtained its first commerce overview, and it was not overview. She was actually upset about it. She was like, “This doesn’t have an effect on the standard of this guide, and I’m actually mad about this.” And the overview actually honed in on a number of the brutal racist moments my character endures from her household, and likewise from the surface. And the reviewer was indignant about it. And I’m not going to say that I used to be blissful about getting a foul overview, however I believe as an adoptee, and somebody who has been in battle with mother and father, and different white people, and has had a lot of conversations with white adoptive mother and father, I knew penning this guide was going to harm some emotions, and trigger some push again – particularly from white adoptive mother and father about what they imagine to be the expertise of my character, or Black adoptees rising up in white households. So, my response to my editor was, “Yeah, that’s a bummer, however this guide wasn’t for them.”

ML: Properly, I believe that’s additionally the onerous a part of navigating the publishing trade as an adoptee author, and as a BIPOC adoptee author. Hopefully, you discover an editor that you simply really feel secure with and cozy with, however you don’t know alongside the method whose emotions may get harm by the nuanced experiences that you simply’re placing into your characters. I’ve a very good relationship with my editor, however I believe she was stunned when For Black Ladies Like Me obtained its first commerce overview, and it was not overview. She was actually upset about it. She was like, “This doesn’t have an effect on the standard of this guide, and I’m actually mad about this.” And the overview actually honed in on a number of the brutal racist moments my character endures from her household, and likewise from the surface. And the reviewer was indignant about it. And I’m not going to say that I used to be blissful about getting a foul overview, however I believe as an adoptee, and somebody who has been in battle with mother and father, and different white people, and has had a lot of conversations with white adoptive mother and father, I knew penning this guide was going to harm some emotions, and trigger some push again – particularly from white adoptive mother and father about what they imagine to be the expertise of my character, or Black adoptees rising up in white households. So, my response to my editor was, “Yeah, that’s a bummer, however this guide wasn’t for them.”

SG: I really like that response.

ML: I’m open to constructive suggestions, it’s not that my books are excellent, however I believe I hit a nerve. After which, I’ve learn some Goodreads opinions of that guide, and other people don’t self-identify as white adoptive mother and father, however they’re mad that the adoptee’s story isn’t the frequent narrative they’ve of their thoughts.

SG: You may normally inform instantly – white adoptive mother and father don’t perceive that. It’s like, “Okay, we all know ya’ll!” We all know the tenor of the so-called ‘critique,’ which is de facto about their very own points and their very own investments in whiteness, and a sure narrative of the white household as savior. So, in some sense when you’re not reproducing that, that’s once you’re going to get these sorts of responses.

SG: One factor I discuss with different BIPOC adoptee writers about, a few of whom are within the anthology I edited with Nicole Chung, When We Change into Ours, is the way in which during which tropes of adoption are used largely by non-adoptee writers in not subtle or attention-grabbing methods. There’s all these different methods you can narratively discover the nuances of adoption, however folks will simply be like, “Oh, this individual is mentally in poor health or has psychological issues, and that’s as a result of they had been adopted!”

SG: One factor I discuss with different BIPOC adoptee writers about, a few of whom are within the anthology I edited with Nicole Chung, When We Change into Ours, is the way in which during which tropes of adoption are used largely by non-adoptee writers in not subtle or attention-grabbing methods. There’s all these different methods you can narratively discover the nuances of adoption, however folks will simply be like, “Oh, this individual is mentally in poor health or has psychological issues, and that’s as a result of they had been adopted!”

ML: I do know! I used to be going to say that that’s additionally a trope: The f’d up adoptee character who has all these issues, and it’s simply due to their adoption. However there’s no nuance as to what’s actually happening right here. I’ve truly seen this with writers who usually are not white and never adoptees, it’s romanticized. They suppose: “Wouldn’t or not it’s cool to seek out out I had a complete different household.” Or, “Wouldn’t or not it’s cool to seek out out I used to be adopted?”

SG: Oh my God. Individuals say that, and also you’re similar to, “Cease.”

ML: I don’t suppose that’s all the time ill-intentioned, however I do suppose it’s a story entice that typically authors of all races who aren’t adopted fall into in the event that they’re not conscious of or have by no means spoken to an grownup adoptee. They’ll be like: “Properly, this can be a cool factor I can put in my story. Or perhaps a dramatic factor I can put in my story. Or perhaps it could be enjoyable so as to add a secret sister!” With out occupied with what that actually means for the character, or for individuals who have grown up in that exact state of affairs. I see this on TV, too.

SG: Oh, it’s throughout.

ML: Like, I’ll be watching a present, and the entire sudden I’ll be like, “Oh no.”

SG: You wish to tear your hair out. Like, “This once more?!” And I’ve to say in kidlit although, particularly in center grade, the orphan trope. Much less so in YA…And writers who I really feel like have a essential lens on different issues, like race, gender, sexuality, class, nationality. However out of the blue on the subject of termination of parental rights…I believe it’s as a result of as I perceive it, a number of kidlit again within the day was like, “Properly, it’s a must to have the youngsters on their very own in your tales to make them good.” So then it was like, “Oh, what an effective way to try this by making them orphans!” And it’s like, “No.” [laughs]. There’s so many layers that should be unpacked. And it’s most likely an unpopular opinion, however it’s simply unhealthy writing.

ML: Properly, it’s unhealthy writing, and it’s not curious in any respect. And it’s additionally actually irritating for me to come across tales the place the one factor about that character is that they’re adopted. It’s clearly an essential factor, however there’s so many layers to a personality. And if the one a part of the character is that they’re adopted, they usually’re effective with it, they usually have twice the love, that’s boring – on only a writing degree, that’s boring.

SG: It’s!

I consider any person like Stefany Valentine, in her story “Nearly Shut Sufficient,” in When We Change into Ours, and he or she turns the adoptee expertise into this stunning and unusual metaphor. Of this woman who’s residing on Earth sooner or later, however she’s from a moon colony. Her adoptive mother and father are from a special moon colony, they’re not “white” on this manner, they’re not native to Earth both, in order that they’re “nearly shut sufficient.” However they’re not. Which mimics Stefany’s expertise as I perceive it, of half-white, half-Vietnamese TRA. That’s actually attention-grabbing! That’s a very attention-grabbing strategy to discover all these fissures and nuances and connections.

ML: Sure, it’s! And that’s the issue— when you’re not writing from expertise, or your solely understanding of adoption is from watching This Is Us, you’re going to overlook alternatives for the sort of nuance and creativity Stefany writes so expertly into her story.

So, you requested a query earlier about how will we, as adoptees and allies, mobilize round this challenge of adoptee illustration in kidlit…I really like and recognize once you submit on social media about books with adoption themes which can be popping out, and name folks in who’re working on this space.

SG: [laughs] Typically I’m wondering if I’m making myself a pariah, however at this level, I’m 49 years outdated, I’m a mid-career author, and I don’t actually care. I’m similar to, I can do that in a pleasant and respectful manner, hopefully, however simply to be like, “It is a drawback, writers and publishing!” And in addition, to allow them to know that we’re watching. I’m not going to sit down right here and fake that I don’t see this, and that that is okay with me. As a result of the place does that get us?

SG: [laughs] Typically I’m wondering if I’m making myself a pariah, however at this level, I’m 49 years outdated, I’m a mid-career author, and I don’t actually care. I’m similar to, I can do that in a pleasant and respectful manner, hopefully, however simply to be like, “It is a drawback, writers and publishing!” And in addition, to allow them to know that we’re watching. I’m not going to sit down right here and fake that I don’t see this, and that that is okay with me. As a result of the place does that get us?

ML: I don’t understand how we mobilize, however I do suppose that us being right here, being loud and speaking about it counts…it’s additionally work and emotional labor. However I believe a number of the time, folks simply haven’t thought critically in any respect about adoption, due to the narratives we’re fed.

I’m married to somebody who has mentioned, “Yeah, earlier than we obtained right into a relationship, I had a really slim understanding of adoption. And I’ve educated myself, and realized lots.” So, most individuals simply don’t suppose past: “Oh, this child wants a house, they usually get saved,” or no matter. Most individuals simply don’t have a essential lens. So, after they encounter a narrative that’s written by an adoptee and is nuanced, it’s jarring. Like, persons are mad that For Black Ladies Like Me has a dad or mum in it who has a psychological well being disaster. And I’m like, “Oh, so that you don’t suppose that there are kids who’re adopted who’re rising up with mother and father who’re combating psychological sickness? Or are narcissists? That doesn’t exist?!”

SG [Laughs] No! There aren’t any narcissists wherever in American tradition!

ML: So, it’s simply ongoing conversations with folks. I’m additionally a queer individual, however in some methods I really feel like I’m all the time popping out as an adopted individual. Or, I’ll discover myself at a desk with folks they usually’re like, “Oh, my son and his spouse are adopting.” So, it’s in all places. And the response is all the time “Oh, you’re so courageous,” or “that’s such an exquisite factor you’re doing for a kid.” And I believe a part of the pushback is that folks get defensive about how a lot they don’t know. We now have to say, “That’s truly actually a one-dimensional understanding of what adoption is. Do you’ve gotten any buddies who’re adopted? Have you ever talked to them about that?”

So, I believe one of many solutions to combatting this one-dimensional adoptee narrative is extra of us, writing our tales, or getting revealed, or publishing ourselves, or in search of group and platforms that may spotlight our work. I believe the work that you simply’re doing, and the anthology is so essential. Doing issues like penning this weblog submit additionally helps. After which after we encounter people who find themselves even barely open, if we’ve got the power and capability, to only be like, “Properly, when you learn that guide, perhaps do this different one.”

I additionally suppose speaking to younger folks in generations which can be developing is essential. I really feel like that’s why it’s essential to put in writing for younger folks in some capability. The issues that younger folks decide up on in my tales that adoptive mother and father and adults don’t decide up on is fairly astounding. It’s irritating that grownup readers and publishing consultants can’t appear to be as open as youngsters.

SG: I imply, publishing is a large number, been a large number. On the identical time that you simply’re making an attempt to do that factor, you’re in it, in some methods you’re complicit, you even have to know that publishing isn’t the rationale why you’re telling these tales. And that then makes it simpler so that you can actually write them in ways in which may make sure people who find themselves gatekeepers and have a number of energy in publishing, it’d make them uncomfortable.

One factor I do really feel like has occurred extra, is when folks see somebody such as you or me, mid-career writers, and different TRA and BIPOC adoptee writers will come as much as me and ask for recommendation. And I believe that’s actually helpful, so that folks know, “Okay yeah, I’m getting this pushback. I’m getting stonewalled, however this individual did it. So, there’s methods round it.” I’m so glad that there’s adoptee work like Mark Oshiro’s—

ML: And Meredith Eire’s.

SG: Proper! The place even 10 years in the past, there weren’t as many people doing this work. And yearly there’s extra of us.

ML: The factor I really like about there being extra of us yearly is that there are positively frequent threads in our experiences, however we’re all particular person folks. Adoptees usually are not a monolith. I believe that the extra of our tales that get on the market, the much less adoptive mother and father will take a look at our fictional or hybrid tales and be like, “Oh, this can be a parenting guide.” They actually appear to suppose, “If I simply learn each story from When We Change into Ours, then I’ll know precisely how my adopted Black little one is feeling, after which I’ll have the reply, and I received’t should take care of these items (this race stuff, or this adoptee stuff).” And the purpose we try to make as adoptee writers is, there are commonalities that enable us to be seen by one another, however no, we’re not all the identical and we’re discovering modern, artistic methods to share these nuances—we’re writing fiction, we’re additionally writing poetry. And that’s essential, too – that outlet.

___

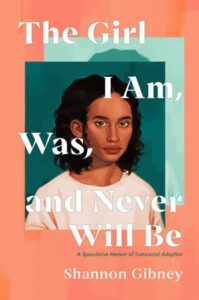

Shannon Gibney is a author, educator, activist, and the writer of See No Colour (Carolrhoda Lab, 2015), and Dream Nation (Dutton, 2018) younger grownup novels that received Minnesota E book Awards in 2016 and 2019. Gibney is college in English at Minneapolis Faculty, the place she teaches writing; she was not too long ago chosen as one in all three Educators of the 12 months in all the Minnesota State Faculty and College system. A Bush Artist and McKnight Writing Fellow, her novel, The Lady I Am, Was, and By no means Will Be, explores themes of transracial adoption by means of speculative memoir (Dutton, 2023) and received a Michael L. Printz Honor. Gibney’s different latest publications embrace the image books Sam and the Unbelievable African and American Meals Struggle (College of Minnesota Press, 2023), and The place We Come From (Lerner, 2022; coauthored), and a YA anthology of tales by adoptees about adoptees, co-edited with Nicole Chung (HarperTeen, 2023).

Mariama J. Lockington is an adoptee, writer, and educator. Her middle-grade debut, For Black Ladies Like Me, earned 5 starred opinions and was a At present Present Finest Children’ E book of 2019. Her sophomore middle-grade guide, In The Key of Us, is a Stonewall Honor Award guide and was featured within the New York Occasions. Her debut younger grownup novel, Ceaselessly is Now, is the 2024 winner of the Schneider Household E book Award. Mariama holds a Masters in Schooling from Lesley College and a Masters in High quality Arts in Poetry from San Francisco State College, she calls many locations house, however at the moment lives in Kentucky along with her spouse and an abundance of vegetation. When Mariama isn’t writing, she works because the Director of the Skilled Studying Sequence on the College of Kentucky’s Faculty of Schooling.